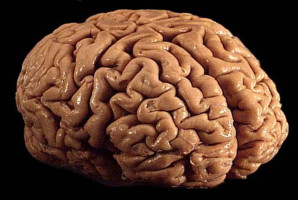

A clinical trial has found that selinexor, the first of a new class of anti-cancer drugs, was able to shrink tumours in almost a third of patients with recurrent glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer.

“Glioblastoma is an incurable brain cancer that needs new therapeutic approaches. Considering that few treatments have any measurable effect on recurrent glioblastomas, the results are encouraging,” says the study’s leader, Andrew B. Lassman, MD, the John Harris Associate Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and chief of the Neuro-Oncology Division at Columbia University Irving Medical Center/NewYork-Presbyterian.

“The drug induces a response in certain patients, and several trial patients stayed on selinexor for more than 12 months, including one for over 42 months,” Lassman adds.

The study was published in Clinical Cancer Research.

Glioblastomas are typically treated with a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and sometimes an electrical device, but the average survival time is just 12 to 18 months.

Selinexor, an oral medication, inhibits, exportin-1 (XPO-1), a major exporter of proteins from the nucleus to cytoplasm that is overexpressed in many cancers, including glioblastoma.

Exportin inhibition results in retention of various tumour suppressor proteins in the nucleus, inducing reactivation of tumour suppressor function as well as other antineoplastic effects.

Selinexor was approved by the FDA for the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma and relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and showed preclinical activity against glioblastoma models.

Lassman led the international phase 2 trial to identify the optimal dosing schedule and evaluate the safety and efficacy of selinexor in adults with recurrent glioblastomas whose cancer had progressed following initial treatment.

Reduction in tumour size was observed in 28% of patients, and a tolerable dose was identified for future human trials already ongoing at Columbia and collaborating sites.

The most common treatment-related side effects were fatigue (61%), nausea (59%), decreased appetite (43%), and low platelet counts (43%). All these side effects were manageable with supportive care and dose modification.

A robust series of molecular studies also were performed, including an effort led by Andrea Califano, Dr., chair of the Department of Systems Biology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, to identify a molecular signature in tumour tissue that may predict which patients would benefit from selinexor.

Lassman, Califano, and others are planning a subsequent study to validate this signature in a subsequent trial of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma.

“Taken together, we believe that our findings show that selinexor is an active drug in some patients with glioblastoma and is worthy of further study,” says Lassman, who also is associate director for clinical trials at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center.

A clinical trial at Columbia is currently evaluating the safety and efficacy of selinexor in combination with other therapies for patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent glioblastoma.