Pancreatic cancer has a lot of nerve.

Notoriously tricky to detect, the disease also often resists traditional therapy.

So, researchers are urgently looking for new ways to disrupt tumour formation.

Though scientists know that the nervous system can help cancer spread, its role in the disease’s earliest stages remains unclear.

“One phenomenon that is known is called perineural invasion,” says Jeremy Nigri, a postdoc in Professor David Tuveson’s lab at Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory (CSHL).

“This means cancer cells will migrate within the nerve and use the nerve as a way to metastasise.”

Now, Nigri and his colleagues at CSHL have discovered that the nervous system plays an active part in pancreatic cancer development, even before tumours form.

Using 3D imaging, they found that tumour-promoting fibroblasts called myCAFs send out signals to attract nerve fibres.

The myCAFs and nerve cells then work together within pancreatic lesions to create a favourable environment for cancer to grow.

The findings are reported in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

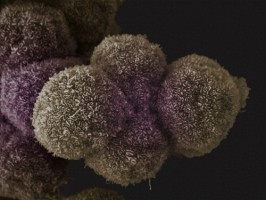

A technique called whole-mount immunofluorescence enabled Tuveson’s team to take 3D photographs of the lesions and surrounding cells.

Where standard 2D images show thin nerve fibres as scattered tiny dots, the 3D images reveal a dense network of nerves snaking through and around the myCAFs and lesions.

“When we first saw this picture, I was shocked,” Nigri says.

“I couldn’t even imagine the lesion like this. I’d only ever seen it in 2D.”

Nigri and his colleagues ran a series of experiments on mice and human cells that uncovered a vicious cycle between myCAFs and nerves.

They found myCAFs give off signals that attract nerve fibres from the sympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for our fight-or-flight response.

These nerve fibres release the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, which binds to the fibroblasts and triggers a calcium spike that further activates myCAFs.

This spike not only promotes pre-cancerous growth, but also pulls in even more nerve fibres, locking the system into a dangerous self-reinforcing loop.

“In one experiment, we use a neurotoxin to disable the sympathetic nervous system,” Nigri says.

“We show reduced fibroblast activation and a nearly 50% reduction in tumour growth.”

Because the myCAF-nerve loop happens so early, disrupting this cycle could lead to potential new therapies.

The findings suggest that clinically available drugs, including doxazosin, may be effective when combined with standard treatments like chemotherapy or immunotherapy.

“The next step will be to study this more in detail and try to find a way to block the crosstalk between fibroblasts and nerves,” Nigri says.

“With support from groups like the Lustgarten Foundation and Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, we hope to one day help improve patient outcomes.”

Source: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

We are an independent charity and are not backed by a large company or society. We raise every penny ourselves to improve the standards of cancer care through education. You can help us continue our work to address inequalities in cancer care by making a donation.

Any donation, however small, contributes directly towards the costs of creating and sharing free oncology education.

Together we can get better outcomes for patients by tackling global inequalities in access to the results of cancer research.

Thank you for your support.