Researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, have worked with investigators at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard to uncover the immune basis for checkpoint myocarditis—a dangerous form of heart inflammation that can occur as a side effect after a patient has been treated for cancer using immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy.

The team identified specific changes to the heart and pinpointed factors in the blood that may indicate whether a patient’s myocarditis is likely to lead to death.

These insights could help refine ICI anti-tumour treatment to minimise risk of side effects while still aggressively attacking cancer cells.

Results are published in Nature.

“We don’t have great solutions now to help these patients, so we try everything to shut down the immune system and reverse checkpoint myocarditis, but that’s an imprecise approach that comes with its own risks,” said study co-senior authorAlexandra-Chloé Villani, PhD, an investigator in the Krantz Family for Cancer Research and the Center for Immunology and Inflammatory Diseases at MGH, and an institute member at the Broad Institute.

“Our results provide a more detailed picture of what’s happening in the heart and suggest intriguing new ways forward to improve patient care.”

The results are among the earliest translational findings to come from the Mass General Cancer Center’s Severe Immunotherapy Complications (SIC) Service and Clinical-Translational Research Effort.

This effort focuses on improving the diagnosis, treatment, and understanding of serious immunotherapy complications that can result from novel therapies that enhance the body’s immune system’s ability to attack tumour cells, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs).

The team focused on checkpoint myocarditis for this project because despite being one of the rarer complications from ICIs—it occurs in roughly 1 percent of patients treated with an ICI—it is the deadliest.

Checkpoint myocarditis leads to dangerous cardiac events such as arrhythmia and heart failure in 50 percent of patients who develop it, and about a third who develop the condition will die from it, despite current treatments.

Importantly, these findings provide the first evidence for an immune reaction in the heart that is distinct from the immune response in the tumour, suggesting that targeted treatments in the future might be able to address checkpoint myocarditis while allowing patients to continue receiving potentially life-saving anti-tumour immunotherapy.

The results also highlight possible therapeutic targets that bolster the rationale behind an ongoing clinical trial recently launched at MGH that is testing an arthritis drug, abatacept, to control this kind of heart inflammation.

“Myocarditis from immune checkpoint inhibitors is a major hurdle for us clinically,” said co-senior author Kerry Reynolds, MD, the clinical director of inpatient oncology at MGH, director of the SIC Service, and an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “This study leads the way to unearthing the roots of these complications.”

“This work provides a biological foundation for testing more targeted therapies for myocarditis due to an immune checkpoint inhibitor. This paper is a major step forward as we need to improve our understanding of this toxicity and this will lead to improved outcomes,” said co-senior author Tomas Neilan, MD, MPH, director of the Cardio-Oncology Program and co-director of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at MGH.

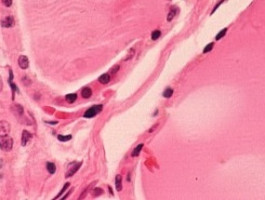

In the new study, the researchers collected blood from individuals who developed myocarditis while on ICI therapy and consented to be part of the study, along with paired heart and tumour tissue from some.

As patients underwent diagnostic procedures at the SIC Service, or after they succumbed to the illness, samples were taken and rapidly sent to the Villani lab, where the research team performed tests to identify the cells and signaling pathways involved in driving and sustaining the inflammatory processes associated with checkpoint myocarditis.

The patterns and differences they found shed new light on the distinct cell types and cellular programs that may be contributing to checkpoint myocarditis and suggest ways to better predict outcomes for patients and new potential drug targets to test.

The authors are continuing their work to identify and develop new blood biomarkers predictive of ICI treatment immune related adverse event complications across organ systems, in addition to seeking to nominate new drug targets to treat these side-effects while enabling cancer patients to stay on their immunotherapy.

Villani will be teaming up with colleagues William Hwang, MD, PhD, and David Ting, MD, who are experts in clinical oncology, and immunologist Llyod Bod, PhD. The four scientists, who will be collaborating with Reynolds and Genevive Boland, MD, PhD, are the 2024 recipients of a Quantum Award from the Krantz Family Center for Cancer Research at the Mass General Cancer Center which will allow them to expand their work and build on the momentum from their Nature paper.

“We are now at a tipping point in our research, and this Quantum Award funding will provide an accelerator to propel our findings,” said Villani.

“It’s important to remember that immunotherapy drugs are miracle, life-saving medicines, and patients should not be afraid of them. We just need to make them work better so that we can maximise their anti-tumour treatment benefit while minimising the risk of adverse events.”

Source: Massachusetts General Hospital

We are an independent charity and are not backed by a large company or society. We raise every penny ourselves to improve the standards of cancer care through education. You can help us continue our work to address inequalities in cancer care by making a donation.

Any donation, however small, contributes directly towards the costs of creating and sharing free oncology education.

Together we can get better outcomes for patients by tackling global inequalities in access to the results of cancer research.

Thank you for your support.