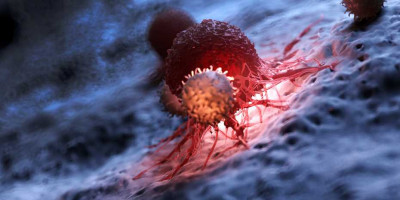

Melanoma skin cancer cells harness a gene usually used by growing nerves to escape from their immediate area and spread through tissues, new research has found.

Scientists found that melanoma cells use the gene ARHGEF9 to create ‘molecular drills’ which help them attach to, and punch holes through, surrounding cells and structures.

These molecular drills, also called filopodia, are also involved in the growth and development of new nerves.

This study shows for the first time that melanoma cells also harness the ARHGEF9 gene to create filopodia and become more invasive.

The scientists hope that in the future ARHGEF9 could be blocked to prevent these molecular drills from forming and to stop cancer cells from spreading.

Scientists from The Institute of Cancer Research, London, grew cells in a bioengineered 3D cell matrix and depleted hundreds of genes one at a time. Using robotic microscopy and sophisticated image analysis, they identified which genes were important for cancer cell shape.

Depleting ARHGEF9 destabilised the molecular drills on the melanoma cells, meaning they were no longer able to attach to and punch holes through surrounding cells. It also lessened cells’ ability to change shape.

The researchers believe that targeting ARHGEF9 could in future lead to treatments that prevent cancer from spreading.

The research was funded by The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) itself, which is both a research institute and a charity, and Cancer Research UK.

The ICR study was published in the journal iScience.

There are more than 16,000 new cases of melanoma in the UK each year, and cases continue to rise. Since the early 1990s melanoma rates have more than doubled.

When melanoma cancer is diagnosed in its earliest stages, it can usually be effectively treated with surgery. It becomes much more difficult to treat as it becomes more aggressive, starts to move through tissues, and spreads to other parts of the body.

ARHGEF9 usually plays a role in setting up connections between nerves during the development of the nervous system. When ARHGEF is not working properly in the nervous system it can lead to epilepsy, and neurodevelopmental disorders like hyperactivity, anxiety, and autism-like traits.

The researchers say the gene is likely to be involved in the growth and spread of other cancer types - particularly neuroblastoma, a type of cancer that stems from nerve tissue and mostly affects children.

Professor Chris Bakal, Professor of Cancer Morphodynamics at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

"Our work shows that melanoma cells borrow use of ARHGEF9 from nerve cells to change shape, branch out and invade new tissues. It’s incredibly important that we understand how cancer cells change their shape to become more aggressive and invasive. When cancers metastasise, they become much harder to treat.

“We’re working to better understand how cancer cells change shape and invade new tissues, so that one day we can find treatments that stop it. Our next step will be to look at the broader impacts of blocking ARHGEF9 to explore whether it could be suitable to target it with a drug to stop the gene from helping the cancer to spread.”

Professor Clare Isacke, Dean of Academic and Research Affairs, at The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said:

“The majority of cancer deaths occur because cancer has spread from the original tumour to other parts of the body, making the disease much harder to treat effectively.

“This research has made a fundamental discovery about how melanoma cells manipulate their shape to become invasive – the first step towards metastasis.

Although it is early research, and more work needs to be done, by understanding more about how skin cancer spreads, we could open up new avenues for developing treatments which stop cancer in its tracks.”

Dr Sam Godfrey, Research Information Team Lead at Cancer Research UK said:

“Discovery research like this is vital. By understanding how cancer evolves and spreads, we can learn how to stop it. Every day in the UK, six people die from melanoma; we urgently need to find new ways to treat this disease.

“It’s encouraging that the team have a new target for further study. These findings will allow future research to focus on the role of this target in melanoma, and whether it could also help us beat certain cancers affecting children and young people. Understanding more about the biology of this disease will lead to new tests and treatments for people with melanoma.”

Source: ICR