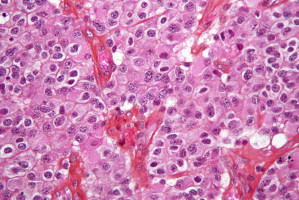

A Ludwig Cancer Research study has identified a metabolic vulnerability in the aggressive and incurable brain cancer glioblastoma (GBM) and shown how it can potentially be exploited for therapy.

The study, led by Paul Mischel of Ludwig San Diego and Benjamin Cravatt of The Scripps Research Institute, demonstrates that GBM cells import vast amounts of cholesterol to survive and that the mechanisms they use to do so can be specifically and effectively undermined with drug-like molecules currently in clinical development.

Their paper appears in the current issue of Cancer Cell.

Although the GBM genome and the mutated genes--or oncogenes--that drive the cancer have been extensively characterised, drugs selected on the basis of such analyses have yet to prove any benefit to GBM patients.

Many of the targeted therapies evaluated so far in trials barely cross the blood-brain barrier and the poor dosing this causes often promotes drug resistance in the tumour.

"Researchers have been thinking about ways to deal with this problem," says Mischel. "One such approach stems from the observation that oncogenes can rewire the biochemical pathways of cells in ways that make them dependent on proteins that are not themselves encoded by oncogenes. Targeting these 'oncogene-induced co-dependencies' opens up a much broader pharmacopoeia, including the use of drugs that aren't traditionally part of cancer drug pipelines but have better pharmacological properties."

The brain's unique systems for cholesterol regulation seemed to be a good place to start looking for such targets.

About 20% of the body's total cholesterol is found in the brain, but none of it comes from outside the organ.

Instead, brain cells called astrocytes make most of the brain's cholesterol, which is an important constituent of cell membranes and the insulation of nerve fibers, and a building block for many signalling molecules.

The researchers showed that GBM cells are extremely dependent on imported cholesterol, as they don't make their own and they need lots of it to keep multiplying.

The cancer cells make sure they keep getting it by shutting down their import controls.

When normal cells have sufficient cholesterol, they convert some of it into molecules known as oxysterols.

These molecules activate a receptor in the cell's nucleus called the liver X receptor (LXR), which helps halt the uptake of cholesterol.

"So when normal cells get enough cholesterol, they stop making it, stop taking it up and start pumping it out," says Mischel. "We found that in GBM cells, this mechanism is completely disrupted. They're like parasites of the brain's normal cholesterol system. They steal cholesterol and don't have an off switch. They just keep gobbling the stuff up."

The researchers showed that GBM cells do this by suppressing the production of oxysterols, thus ensuring that their LXRs remain inactive.

Working with Ludwig's Small Molecule Development team led by Andrew Shiau and including Tim Gahman, they identified an experimental metabolic disease drug candidate named LXR-623 that activates LXRs.

After showing that it easily crosses the blood-brain barrier in mice, they examined its effect on GBM tumours derived from human patients that were implanted in mice.

"Disrupting cholesterol import by GBM cells caused dramatic cancer cell death and shrank tumours significantly, prolonging the survival of the mice," says Mischel. "The strategy worked with every single GBM tumor we looked at and even on other types of tumours that had metastasised to the brain. LXR-623 also had minimal effect on astrocytes or other tissues of the body."

The GBM treatment strategy they've devised, Mischel notes, could be implemented in trials using related drugs that are under development or in early clinical trials.

Source: Cancer Cell

The World Cancer Declaration recognises that to make major reductions in premature deaths, innovative education and training opportunities for healthcare workers in all disciplines of cancer control need to improve significantly.

ecancer plays a critical part in improving access to education for medical professionals.

Every day we help doctors, nurses, patients and their advocates to further their knowledge and improve the quality of care. Please make a donation to support our ongoing work.

Thank you for your support.